"Here is 'Rosalind'": Zelda’s Photograph and F. Scott Fitzgerald's Letter to a Fan

From autumn 1920 until spring 1921, Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald and F. Scott Fitzgerald, newlyweds, were living at 38 West 59th Street in New York City. In the wake of the great success of his first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920), Fitzgerald was working quickly on a second, The Beautiful and Damned, to be published as soon as possible.

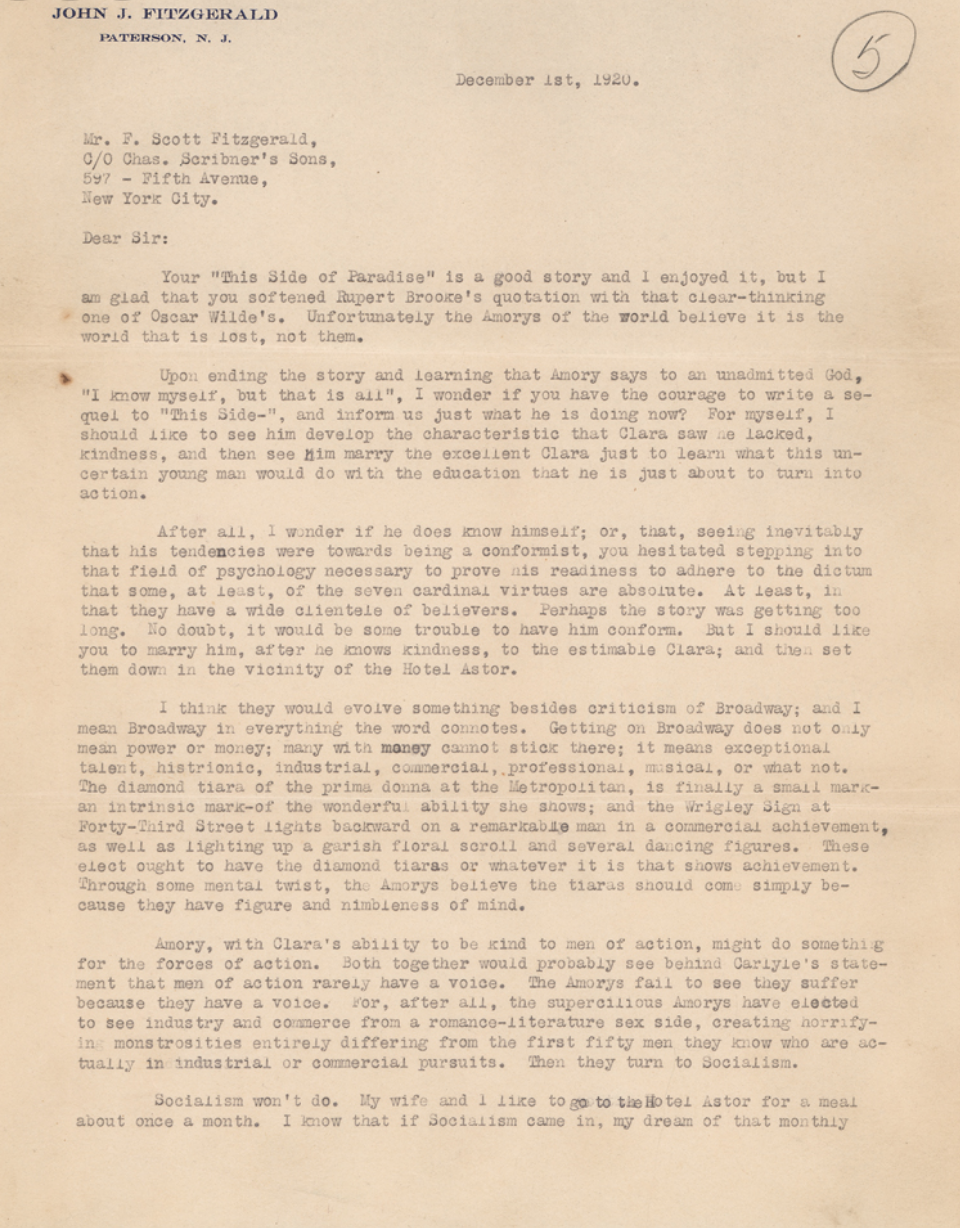

John J. Fitzgerald, an accountant in Paterson, New Jersey — and no relation to Scott — read This Side of Paradise, and wrote to Fitzgerald about it on December 1, 1920. The young writer — Fitzgerald was 25 — replied to him in a detailed letter that has resurfaced and is being sold, together with a remarkable photograph, by RR Auction of Boston, Massachusetts. Offered in 2009 by Swann Galleries in New York City, the letter and photograph swiftly went back into private hands. John Fitzgerald’s letter has never been reproduced, in part or in full. RR Auction posted the lot yesterday as part of an online auction concluding January 13, 2021.

John had this initial question for Scott: “Upon ending the story and learning that Amory says to an unadmitted God, ‘I know myself, but that is all’, I wonder if you have the courage to write a sequel to ‘This Side’, and inform us just what he is doing now?” John had a suggestion: “I should like you to marry him, after he knows kindness, to the estimable Clara; and then set them down in the vicinity of the Hotel Astor.” John foresaw a success on Broadway for Scott’s characters, which would surely have intrigued Fitzgerald — he always wanted to be a playwright, in his younger and more vulnerable years. Wrote John, “Getting on Broadway does not only mean power or money; many with money cannot stick there; it means exceptional talent, histrionic, industrial, commercial, professional, musical, or what not.” John was particularly bothered by Amory’s rejection of his Catholic faith, and attraction to socialism.

One bit of John’s advice is of singular interest. He suggests a novel in which “keen, efficient, capable, wonderful men and women” put together “great enterprises requiring trust, confidence, and understanding of each other,” thereby “mak[ing] the shore line of New York City such a great joy to look at from the standpoint of things done in the world.” Both The Beautiful and Damned (1921-2) and The Great Gatsby (1925), Fitzgerald’s next two novels, are about almost exactly the inverse of this proposal. John closes his letter by stating that he was heading off to read Flappers and Philosophers, Scott’s 1920 collection of stories first published primarily in The Saturday Evening Post.

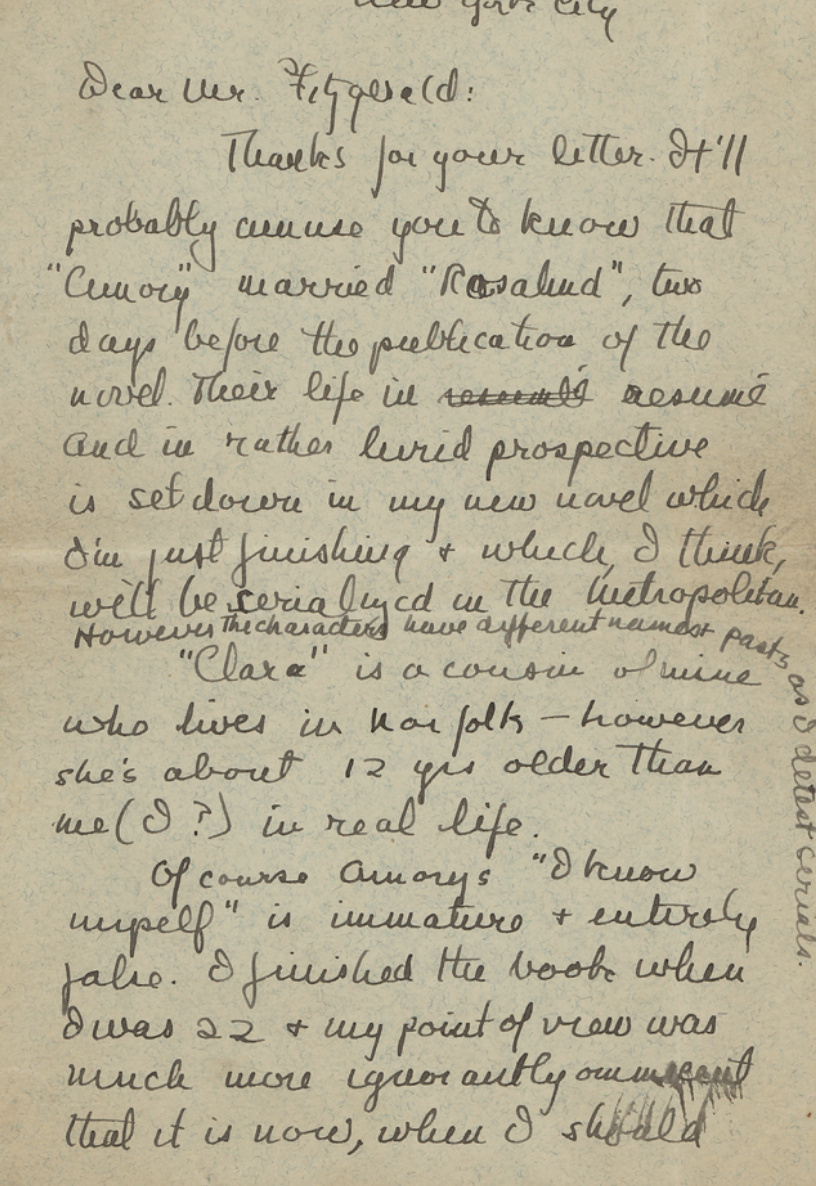

Here is Scott’s reply.

Dear Mr. Fitzgerald:

Thanks for your letter. It’ll probably amuse you to know that “Amory” married “Rosalind,” two days before the publication of the novel. Their life in resumé and in rather lurid prospective is set down in my new novel which I’m just finishing + which I think will be serialized in the Metropolitan. However the characters have different names + pasts as I detest serials.

“Clara” is a cousin of mine who lives in Norfolk—however she's about 12 years older than me (I?) in real life.

Of course Amory’s “I know myself” is immature + entirely false. I finished the book when I was 22 + my point of view was much more ignorantly omniscient than it is now, when I should hesitate to proclaim anything except a pessimistic optimism. Don’t you think your “socialism won’t do” is a bit too certain. Seems to me it contains an echo of the “Democracy won’t do” + “Suffrage won’t do” in other ages.

Of course commercially I am at present a success—probably making as much as any three men in my class at Princeton all together yet in my dealings with either the magazines or the movies or the publishers I have found them, as a class, dull, unimaginative, with a vague philosophy compounded of a dozen or so popular phrases. I have worked when I first left the army, as an advertising man at $90 a month and a car repairer and was extremely disgusted at being one of the exploited hogs in either hog-pen.

I can see from your letter that you are a Catholic. I was a very strong one, very nearly a priest, and then when adversity really came + I struggled out of it it seemed that it was at first myself I must look to. My favorite writers are now Conrad, Haeckel + Nietche + Anatole France—of Americans H. L. Mencken.

Except for Benediction, The Ice Palace, + The Cut Glass Bowl my collection of stories is trash—to tickle the yokelry of Kansas and get enough money to live well. I doubt if I shall ever do such stuff again. “Darcy” was Sigourney Fay, a monsignori + my best friend. When he died the church became an utterly unreal but beautiful story to me.

I am utterly cynical about any moral law or the need of any. The one thing I am sure of is my love of beauty + even that fades + passes.

I’ve answered your letter at length because tho I still get two or three a day from readers it’s very seldom that one is any more than a gushing pangyric (sp!).

Sincerely

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Fitzgerald’s criticisms of his own work, reflections on the publishing industry and on his past employment, and opinion of his own short stories collected in Flappers and Philosophers are cuttingly keen. His brash tone is of a piece with other letters he wrote at the time; though it amused him to refer to his short stories as “trash,” he would privately admit in 1925 to H.L. Mencken, the American author he says here he most admires, that “my whole heart was in my first trash.” Fitzgerald’s passing defense of socialism is interesting, in that his fascination with Marxism and Russia would flower in an idealistic way in the early 1930s. His discussion of Catholicism, and the effect upon him of the death in January 1919 of Cyril Sigourney Fay, who succumbed to influenza during the pandemic, and to whom This Side of Paradise is dedicated, has not been put so succinctly or elegantly in anything previously published.

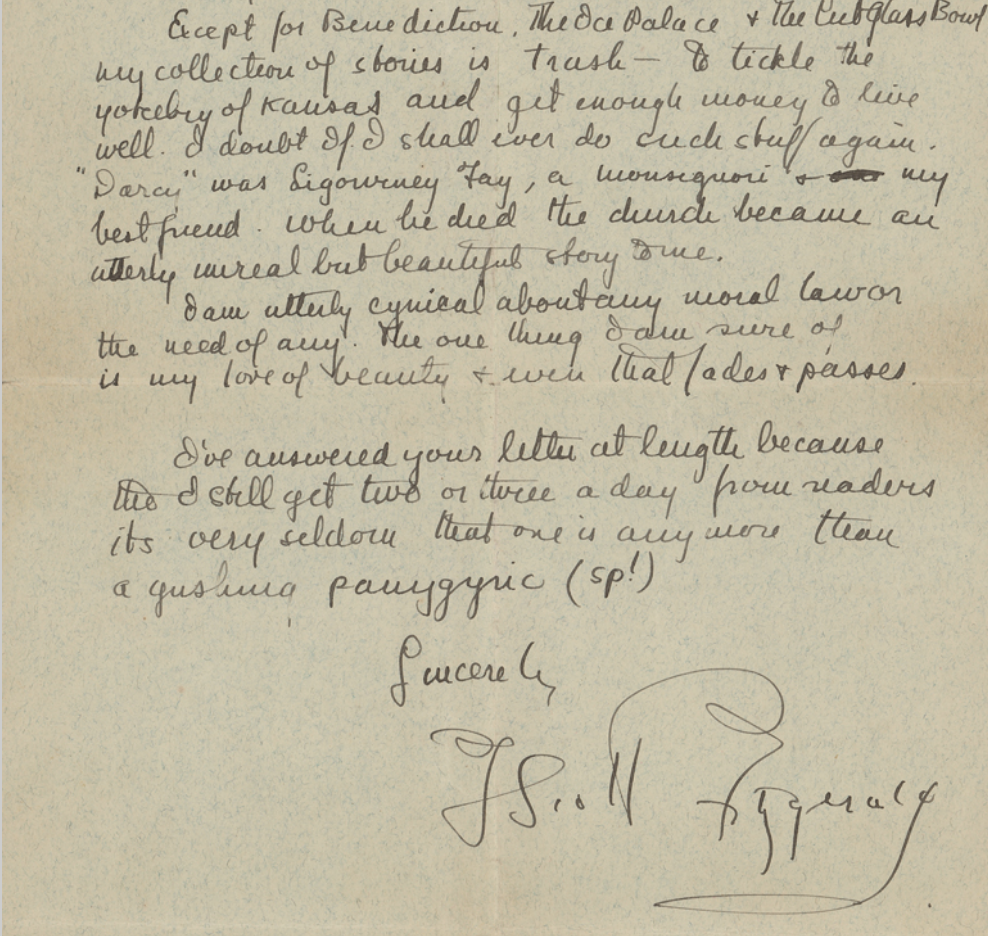

Lastly, and most compellingly, while the relation of real people to the fictional ones they inspired is hardly new to Fitzgerald critics, the photograph included in this auction lot is one of a kind, to say the least. Autobiographical parallels between Fitzgerald’s life, and his novels and short stories, are standard in criticism of his writings, and in biographies of Fitzgerald. That there’s a lot of him in Amory Blaine, the arrogant, muddled young protagonist of This Side of Paradise, was recognized immediately; later, Fitzgerald would refer to Amory as his younger brother. Fitzgerald’s mention here that his favorite cousin Cecilia Delihant Taylor, who was a decade his senior and lived in Norfolk, Virginia with her family, is the model for Clara Page, Amory’s widowed distant cousin, is eye-catching to see in his own handwriting. And while Zelda Sayre’s presence in Rosalind Connage, the girl Amory loves and loses, has often been noted, the studio portrait of his wife that Scott sent to John — intended, I think, both jocularly and seriously — speaks for itself. The photograph is faded and torn, showing its age, but the 20-year-old Zelda’s eyes are full of light and life, her speaking smile and the shadow of a dimple dazzling. That a curl of her hair under the snug hat has strayed out into the frame is fine: it only enhances just how perfectly young and beautiful she is.

all images courtesy RR Auction

text of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s letter © The Trustees of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Estate